Writing Custom Kubernetes Controllers in Go

Kubernetes controllers are core components that monitor the state of the cluster, make changes attempting to move it towards the desired state, and other housekeeping tasks.

For example, if you create a new Pod the ReplicaSet controller notices the Pod and creates it. Other common built-in controllers include the Deployment, Job, Node, etc controllers.

In this comprehensive guide you’ll learn:

- What Kubernetes controllers are

- When to write a custom controller

- How controllers work under the hood

- Controller patterns and best practices

- Implementing a real-world controller in Go

You’ll come away with the skills to build highly tuned controllers tailored for your applications and infrastructure.

What are Kubernetes Controllers?

Kubernetes controllers are control loops that:

- Observe cluster state from the API server

- Compare actual versus desired state

- Take action to converge to desired state

For example, a ReplicaSet controller ensures the right number of Pod replicas are running at all times.

If nodes fail or Pods die, the controller will notice the difference between actual and desired state, and create new Pods to match the desired count.

Controllers provide continuous reconciliation. They run non-stop, monitoring state and fixing discrepancies.

Out of the box, Kubernetes provides robust controllers for core entities like Deployments, DaemonSets, StatefulSets, CronJobs, Services, etc.

But we can also write custom controllers to extend Kubernetes for our own use cases.

When to Write a Custom Controller

Default controllers cover common needs around workloads, networking, storage, etc. But you may want custom controllers for:

- New resource kinds not in core Kubernetes

- Adding domain-specific logic layered on existing kinds

- Automating bespoke operational or maintenance tasks

- Integrating Kubernetes with external systems

Custom controllers are powerful for automating cluster workflows tailored to your infrastructure needs.

Some examples include:

- Auto-scaling GitLab runners on demand

- Draining nodes based on hardware sensors

- Restricting namespaces based on IAM roles

- Backup/restore/disaster recovery workflows

- Complex job coordination logic

If you find yourself scripting lots of manual Kubernetes tasks, consider consolidating the logic into a dedicated controller.

Next let’s look at how controllers work under the hood.

How Controllers Work

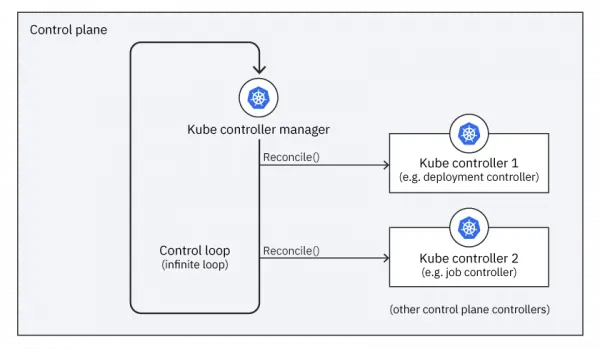

A controller is essentially an automated reconciler between actual and desired system state:

The reconcile loop:

- List and watch for objects of the target kind, e.g.

Pods - For each object, inspect its state

- Reconcile actual state with desired state

- Update the object and/or related objects

Controllers continue this loop indefinitely to provide constant reconciliation.

Multiple controller instances may run, competing for objects. The workload is distributed for scalability.

Controller business logic is encapsulated in the Reconcile() function. It is invoked on every change, allowing controllers to handle even complex state machines.

Next let’s implement a simple controller to see the flow in action.

Implementing a Simple Controller

To demonstrate core concepts, we’ll build a trivial controller to count and log Pod changes:

- Initialize controller manager

- List and watch Pods

- Log Pod creations/deletions

First install the controller-runtime 🔗 library:

go get sigs.k8s.io/controller-runtimeNext create a new Go file main.go:

package main

import (

"context"

"github.com/kubernetes-sigs/controller-runtime/pkg/client"

"github.com/kubernetes-sigs/controller-runtime/pkg/manager"

)

func main() {

// 1. Initialize manager

mgr, err := manager.New(config, manager.Options{})

handleErr(err)

// 2. Create controller

c := &PodCounter{}

// 3. Setup reconciler

err = c.SetupWithManager(mgr)

handleErr(err)

// 4. Start manager

err = mgr.Start(context.Background())

handleErr(err)

}This creates a manager and registers our controller.

// podcounter_controller.go

type PodCounter struct {

client.Client

}

func (c *PodCounter) Reconcile(ctx context.Context) error {

// List Pods

podList := &corev1.PodList{}

err := c.List(ctx, podList)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Log number of Pods

log.Printf("Number of pods: %d", len(podList.Items))

return nil

}Reconcile lists Pods then prints the count.

On each reconcile, it will log the latest Pod number.

To run locally:

# Setup RBAC

kubectl apply -f config/rbac.yaml

# Run manager

go run *.goWe now have a functioning controller!

With each Pod change, it will re-list and log the count.

Next let’s look deeper at real-world patterns.

Common Controller Patterns

Here are some best practices for robust production-grade controllers:

Multiple Queue Keys

Controllers read object updates from a workqueue. By default, one queue is used. For efficiency, use multiple queues based on key functions:

func (c *Controller) enqueue(obj metav1.Object) {

// Hash key function

key := hash(obj) % 10

// Dispatch to queue

queue := c.workqueues[key]

queue.Add(obj)

}This spreads work across queues.

Limits and Backoffs Add work limits and backoff periods to manage queue load:

func (c *Controller) StartWorkers(stopCh <-chan struct{}) {

// Max threads

threads := 2

for i := 0; i < threads; i++ {

go wait.Until(c.runWorker, time.Second, stopCh)

}

}

func (c *Controller) runWorker() {

for obj := range c.queue.Get() {

// Max requeues

if obj.retries >= 3 {

c.queue.Forget(obj)

continue

}

err := c.processItem(obj)

c.handleErr(err, obj)

// Exponential backoff

obj.retries++

c.queue.AddAfter(obj, time.Second*2^obj.retries)

}

}This prevents overloading and retries gradually.

Leader Election Use leader election to ensure only one controller instance handles reconciliation:

import "github.com/kubernetes-sigs/controller-runtime/pkg/leaderelection"

func main() {

// Elect leader

leader, err := leaderelection.NewLeaderElector(election.Options{})

if !leader.IsLeader() {

log.Printf("Not leader, skipping reconciliation")

return

}

// Run controller

mgr, err := manager.New(...)

//...

}This avoids conflicting changes from multiple controllers.

Defaulting and Validation Consider adding schema defaults and validation:

import apiextensionsv1 "k8s.io/apiextensions-apiserver/pkg/apis/apiextensions/v1"

func (c *Controller) SetupWebhook() {

schema := apiextensionsv1.CustomResourceValidation{

OpenAPIV3Schema: &apiextensionsv1.JSONSchemaProps{

// Specify validations

Required: []string{"spec.size"},

Properties: map[string]apiextensionsv1.JSONSchemaProps{

"spec": {

Required: []string{"size"},

Properties: map[string]apiextensionsv1.JSONSchemaProps{

"size": {

Type: "string",

Pattern: "^[0-9]+Gb$",

Default: "10Gb",

},

},

},

},

},

}

// Register webhook

// ...

}This validates custom resources at admission time.

Horizontal Scaling

Control CPU/mem limits and replicas to scale horizontally:

# controller.yaml

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

spec:

replicas: 3

template:

spec:

containers:

- name: controller

resources:

limits:

cpu: 500m

memory: 512MiTune resource limits based on usage. Add more replicas as needed.

Proper instrumentation is also key.

With patterns like these, controllers can manage even large clusters efficiently.

Implementing a Real Controller To demonstrate a practical controller, we’ll build one to auto-scale GitLab runners on demand.

It will:

- Watch for a ScaleRunner resource

- Scale GitLab runner Deployments based on pending jobs

- Remove idle runners by scaling to 0

ScaleRunner Object

apiVersion: autoscaling.example.com/v1

kind: ScaleRunner

metadata:

name: example

spec:

repo: myorg/myapp

min: 2

max: 10Controller Logic

import (

"context"

autoscalingv1 "autoscaling.example.com/v1

kbatchv1 "k8s.io/api/batch/v1"

corev1 "k8s.io/api/core/v1"

"k8s.io/apimachinery/pkg/api/errors"

metav1 "k8s.io/apimachinery/pkg/apis/meta/v1"

)

const runnerName = "runner"

func (c *ScaleRunnerController) Reconcile(ctx context.Context) error {

runner := &ScaleRunner{}

name := client.ObjectKey{Namespace: "default", Name: "example"}

if err := c.Get(ctx, name, runner); err != nil {

return err

}

deploy := &appsv1.Deployment{}

name = types.NamespacedName{Namespace: "default", Name: runnerName}

if err := c.Get(ctx, name, deploy); errors.IsNotFound(err) {

// Create runner deployment

runnerCount := int32p(runner.Spec.Min)

deploy = runnerDeployment(runnerName, runnerCount)

if err := c.Create(ctx, deploy); err != nil {

return err

}

}

// List runner jobs

jobs := &kbatchv1.JobList{}

c.List(ctx, jobs, client.InNamespace("default"))

active := len(jobs.Items)

desired := int32(active) // Scale based on job count

// Enforce min/max

desired = max(desired, *runner.Spec.Min)

desired = min(desired, *runner.Spec.Max)

// Update deployment

deploy.Spec.Replicas = &desired

err := c.Update(ctx, deploy)

return err

}

func runnerDeployment(name string, replicas *int32) *appsv1.Deployment {

// Prepare deployment

//...

return deploy

}This scales runner Deployments based on pending jobs.

Wrap Up

In this guide we covered:

The role of controllers in Kubernetes When to implement custom controllers Controller reconciliation patterns Building a simple logging controller Real-world design patterns Implementing a scaled-down autoscaling controller Controllers are powerful for encapsulating business logic and automation workflows on Kubernetes.

With core libraries like controller-runtime, writing production-ready controllers is straightforward.

The patterns here will help guide you in developing robust, scalable controllers.